The Cochrane Collaboration is an independent network of volunteers, funded only by donations, that collate systematic reviews of the evidence base for healthcare interventions. You can go online and view for yourself the current best thinking on how effective various treatments are. It is an important resource. (And you can help making it free throughout the EU by signing here.)Cochrane does not just cover conventional treatments, but also reviews alternative therapies where such trial data exists. One example is their review of homeopathic Oscillococcinum, which is heavily marketed in France as a cure for la grippe. Every pharmacy in France this winter has had a huge shop window advert showing a ‘flu gripped Frenchman with a red scarf and advertising Boiron Oscillococcinum as the answer for both prevention and treatment. It is popular stuff, and worth millions of Euros to the French pharmaceutical company. And of course it doesn’t work. Oscillococcinum is made from duck’s liver, but diluted so much that one little duck would be enough supply for all of Boiron’s operations for ever and ever, and still have most of the liver left over for a rather delicious paté au foie gras de canard. Fifty million Frenchmen can’t be wrong, can they? What does Cochrane say?

The Cochrane Collaboration is an independent network of volunteers, funded only by donations, that collate systematic reviews of the evidence base for healthcare interventions. You can go online and view for yourself the current best thinking on how effective various treatments are. It is an important resource. (And you can help making it free throughout the EU by signing here.)Cochrane does not just cover conventional treatments, but also reviews alternative therapies where such trial data exists. One example is their review of homeopathic Oscillococcinum, which is heavily marketed in France as a cure for la grippe. Every pharmacy in France this winter has had a huge shop window advert showing a ‘flu gripped Frenchman with a red scarf and advertising Boiron Oscillococcinum as the answer for both prevention and treatment. It is popular stuff, and worth millions of Euros to the French pharmaceutical company. And of course it doesn’t work. Oscillococcinum is made from duck’s liver, but diluted so much that one little duck would be enough supply for all of Boiron’s operations for ever and ever, and still have most of the liver left over for a rather delicious paté au foie gras de canard. Fifty million Frenchmen can’t be wrong, can they? What does Cochrane say?

Cochrane has a review entitled, “Homoeopathic Oscillococcinum for preventing and treating influenza and influenza-like syndromes”, and it concludes,

It is claimed that Oscillococcinum (or similar homeopathic medicines) can be taken either regularly over the winter months to prevent influenza or as a treatment. Trials do not show that homoeopathic Oscillococcinum can prevent influenza. However, taking homoeopathic Oscillococcinum once you have influenza might shorten the illness, but more research is needed.

Now, this is not good news for using Oscillococcinum for the prevention of ‘flu. But is there a slight effect for shortening the illnesses once you have caught it? The review suggests you might feel better about 6 hours sooner if you took the pills. Should we believe this? And, is more research warranted as the Cochrane reviewers suggest? I think the answer to that is that we can be quite confident that, despite these results, there is no effect, and that, despite what the reviewers say, further research would be a waste of time.

Why do I think this? Let me explain how I think about whether a healthcare intervention is quackery or not. The Cochrane reviewers are looking at published clinical evidence for the efficacy of homeopathy. But clinical evidence should only be one factor in assessing the scientific validity of a treatment. The other factor is plausibility, that is, how well our understanding of the treatment fits in with our scientific worldview.

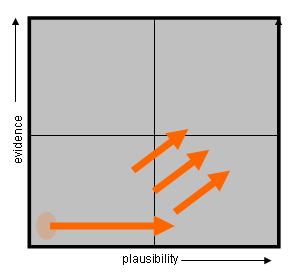

Thinking graphically always aids clarity and so we can costruct a graphical view of the combined impact of evidence and plausibilty on assessing if a treatment is quackery or not. We can plot a treatment’s evidence against its plausibility as follows:

Figure1. The Quackometer Quackery Quadrants

Let’s call this the Quackometer Quackery Quadrants – of course. How would we divide the scales to use on each axis? For ‘evidence’, this is not too hard. There are accepted measures of the degree of evidence available for a treatment. A heirarchy of medical evidence can be constructed as follows:

-

Systematic Reviews of well controlled Randomized Controlled Trials (meta-analysis) or single RCT with narrow CI (confidence interval)

-

Systematic review cohort studies or lesser quality RCTs

-

Case controlled studies (non randomized)

-

Case series (no control group)

-

Expert opinion (GOBSAT – Good Old Boys Sat Around Table)

Can we construct a similar hierarchy of plausibility? That is possible too. We could, for example, take a mathematical approach and assign the axis a Bayesean prior probability scale. This might be the most desirable approach, but largely impractical in that it is difficult to assign meaningful probabilities to hypotheses, such as the homeopathic one, that ‘like-cures-like’. How likely is it that homeopathy will overthrow all that we know about biology? It is vanishingly small, but difficult to be quantitative about it. We can, put a more qualitative scale and grade a treatment according to how well it conforms to well tested knowledge or how much it relies on speculative knowledge or even magical thinking.

-

Proposed mechanism of action based on similar well understood treatments.

-

Consistent with well established biochemistry

-

Consistent with accepted biology and chemistry

-

New biological mechanisms required

-

New chemistry and physics required

-

Inconsistent with accepted physics/chemistry/biology.

-

Requires magical mode of operation/inconsistent with natural laws

You may well come up with your own scale. For the sake of my argument, constructing a definitive and absolute scale is not important. A qualitative approach like the above will do.

So now we have a set of four quadrants that we can use to broadly classify medical interventions according to their plausibility and evidence base. The top right quadrant contains treatments that are well understood in terms of their modes of action and have a good evidence base to support them. The lower left hand quadrant contains interventions that are not based on known science, or rely on pseudoscientific explanations, or even at the extreme magical and supernatural thinking. This is truly the quadrant of quackery.

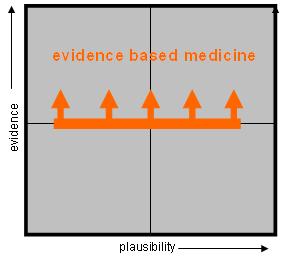

We would like to think that our medical interventions are all nicely housed in the top right hand quadrant, but this is not the case. For example, the Cochrane methodology, in solely looking at the clinical evidence base will allow us to draw a line of ‘evidence based medicine’ that runs horizontally across the quadrants as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Realm of Evidence Based Medicine

Everything above the line can be considered as evidence based and, therefore, worthy of public funding and likely to form effective treatments.

However, the problem with this approach can be illustrated with the quackery quadrants. Such a demarcation could possibly allow treatments that have an evidence base, but that are based on highly implausible mechanisms. Can this situation arise? Of course it can.

When medical evidence is evaluated, it is usually of a statistical nature. An arbitrary cut of point is decided where the confidence limits for acceptance becomes defendable. If we get better statistical results than this cut off then we can say we have a significant result. Usually, this cut-off is set at a 95% confidence limit. You may see this written in papers as the p=0.05 threshold. Any test with a p value of less than 0.05 is determined to be of ‘significance’. Unfortunately, the p values in themselves are not enough to tell us if a particular experiment is giving us reliable information about a medical intervention. The p value merely tells us that if the test was fair and unbiased, then what is the probability that the result was merely due to chance and not due to the effects of the intervention? For a p value of 0.05 this means that 1 in 20 fair tests will give the wrong answer.

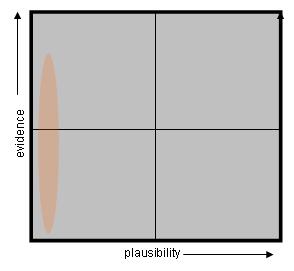

It is worse than that though as it can be very difficult to construct fair tests. Experiments and reviews can have flawed methodology, incomplete controls and blinding, unpublished results, and, in the worse cases, even be subject to fraud and dishonesty. As such, the proportion of experiments and reviws that give the wrong answer will be much worse than 1 in 20. The upshot of this is that for a highly implausible, but popular alternative medical treatment, then many trials will generate a significant fraction of results that show positive results. If we were to plot the distribution of the various elements of homeopathic evidence on our quackery quadrants, we might end up with something like figure 3.

Figure 3. Where Homeopathic Treatments lie in the Quackery Quadrants

With homeopathy, as we are repeatedly told by the homeopaths, there is an evidence base for supporting the efficacy of their treatments for at least some conditions. This is indeed true, but it is insufficient to convince sceptics that homeopathy is anything other than a placebo. We can see that these positive results, such as the small positive effect in the Oscillococcinum result in the Cochrane review, try to force us to accept that we have a genuine effect from a highly implausible treatment. In other words, we are being forced to accept a miracle. The top left quadrant is indeed the quadrant of miracles in that we are being asked to accept something that appears to be against natural laws.

Now science is not well known for its casual acceptance of miracles, and we should definitely not be accepting the evidence of homeopathic trials as evidence of a medical miracle. The philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) was one of the first to describe the conditions by which we should accept the occurrence of a miracle and that is that the probability that the evidence for the miracle is good evidence should be greater than the probability that the evidence is flawed in some way, such as by mistaken testimony, chance or deceit.

In Hume’s words,

When anyone tells me that he saw a dead man restored to life, I immediately consider with myself whether it be more probable, that this person should either deceive or be deceived, or that the fact, which he relates, should really have happened. I weigh the one miracle against the other, and according to the superiority, which I discover, I pronounce my decision, and always reject the greater miracle. If the falsehood of his testimony would be more miraculous than the event which he relates; then, and not till then, can he pretend to command my belief or opinion.

With clinical trials, we have a pretty good idea of what the confidence a trial gives us – typically a 95% confidence level. How confident are we that our basic science of matter is correct? Would you take a 1 in 20 bet that the properties of matter were not to do with atoms? I would suggest that our confidence in basic physics is a lot better than 95% and that homeopathy is in direct contradiction with this knowledge. We have around two hundred years of good research into the properties of matter, collected by thousands of researchers. One little homeopathy study is very unlikely to threaten that body of knowledge. It is much more likely that the positive results of homeopathy are due to statistical chance, poor experimental methodology and even fraud, than showing contradictory evidence for the refutation of fundamental physics.

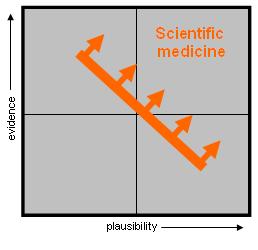

On our quackery quadrants then, we can draw a line that can tell us when we should accept the result of the evidence before us for any particular treatment. That line will run from the top left to the bottom right. What we are doing here is simply graphically illustrating the mantra of sceptics that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. The corollary to this is that mundane, highly plausible and, dare I say, ‘common sense’ claims require a lower standard of evidence.

Figure 4. The Realm of Scientific Medicine. The evidence base for homeopathy is now excluded from scientific medicine, although may well sit within ‘evidence based medicine’

Figure 4 then gives us a quite different view of how to accept the health claims of medicine from the standard one adopted by Cochrane and such bodies as NICE. We are describing scientific medicine as opposed to purely evidence based medicine. Scientific medicine takes into account the scientific context of the evidence and says that we should interpret that evidence in light of what we know about the world. It forbids us from casually accepting light evidence for treatments that are not plausible from what we know about physics, chemistry and biology. We can now only accept the evidence of a treatments efficacy when that evidence is greater then prior probability of that treatment being ineffective. This approach has a number of important implications.

Firstly, and most importantly, to all intents and purposes, clinical trials of highly implausible treatments, such as homeopathy, can never be used as evidence of their efficacy. No matter how good the statistical result of a trial, or how much data is analysed in a meta-analysis, the probability will always be greater that we are just analysing flawed data rather than there being a real effect. Homeopaths complain that sceptics never accept that trial data is proof of the effectiveness of homeopathy. This approach shows that homeopaths are quite right in their fears, although sceptics ought to be careful to point out that it is not because there is no evidence, but rather than the available evidence falls far short of any meaningful threshold of acceptance. Without a degree of plausibility, homeopaths are asking scientists to believe in the daily occurrence of miracles, and that will not do.

This answers my question as to whether Cochrane should be calling for more clinical research. What good would it do if more research was done in Oscillococcinum? More positive results for homeopathy might allow treatments to slip by simplistic ‘evidence based’ criteria for determining effectiveness, but will never satisfy broader scientific scepticism of homeopathy. There is a possible split that exists at the moment where many clinicians working in the NHS provide homeopathy to their patients whilst many academics and scientists are shouting what a nonsense this is. The hospitals are accepting a degree of evidence that is far too weak for real confidence to be expressed in the efficacy of homeopathy. Rather than use a simplistic evidence based approach to deciding which treatments to use in the NHS, a scientific approach needs to be adopted where the prior plausibility of a treatment is first evaluated so that it is possible to decide the degree of evidence required to support that treatment. Not all proposed treatments are the same and can be judged by the same criteria.

By conducting more research, we allow more anomalous evidence to creep in and that can only add to the difficulty of making health care decisions in our hospitals and governments. Rather than clarifying the position, clinical research into highly implausible treatments runs a very high risk of obscuring the truth. It is not that I do not accept that one day a highly implausible treatment will be shown to be effective, but rather there is a far higher chance of producing a nonsense result that just obfuscates the discussion. I will discuss how implausible research should be conducted shortly.

This brings me onto the second point. Homeopaths often accuse sceptics of double standards where low standards of evidence appear to exist for many routine hospital procedures whereas strong evidence is demanded for homeopathy. We can now see that this is not hypocrisy, but an inevitable consequence of scientific thinking. It is perfectly rational to accept treatments as effective if they have very high plausibility but little in the way of good objective evidence. Taking a trivial example, we all know that putting pressure on a wound stops bleeding. But I bet no randomised controlled trials exist to support such a procedure. Would anyone want to doubt that? For many surgical procedures, little in the way of high quality trial data may exist, the evidence may be at worst of the GOBSAT variety. But, many procedures may be inherently less susceptible to biases and subjective measurement errors. Death is a hard measurement point and is not easy to fudge. If a surgical procedure appears to prevent a quick death then we may well be quite right to accept largely anecdotal and case-based evidence. In fact, to insist on randomised controlled trials might well be highly unethical given the high degree of plausibility of the procedure.

This is, of course, in stark contrast to homeopaths claims that their pills can prevent or cure malaria. There is absolutely no good reason to think that this might be true. The plausibility of such a treatment is as near to zero as makes no difference. And yet many homeopaths insist that this is a bedrock of their practice (Hahnemann’s first homeopathic experiments were on malaria). Furthermore, some homeopaths insist on doing their own trials, often in Africa. Such experiments must be totally unethical, because their results, even if positive, could never be sufficient to demonstrate the efficacy of their treatment. Trials such as these put patients at risk with no prospect of any enlightenment to come from that risk.

So, my third point is what sort of research should homeopaths be doing, if any? Well, the only ethical and constructive research that could be done is research that could move homeopathy along the plausibility axis. This would be fundamental research that sought to uncover potential models of how the treatment might work. Before embarking on using real patients as test subject, confidence must be established that a treatment may be effective. That is not just good science but good ethical behaviour.

Figure 5. Direction of Investigations into implausible treatments

Homeopathy has a long path to go along here. Some homeopath supporters recognise this fact and see the importance of both demonstrating their fundamental tenets are true and also trying to show how homeopathy might be integrated into science. (My homeopathy challenge is a simple test to ask homeopaths to demonstrate that their beliefs about the preparation of homeopathic remedies are not just wishful thinking. So far, no one has agreed to the test.) There are some researchers who are looking into so-called ‘memory of water’ effect, that might add a smidgen of plausibility into their claims. So far, the experimental evidence for water memory is woefully inadequate, even if it was in itself a plausible hypothesis.

The utter degree of implausibility is so staggering that I believe it would be difficult to justify public expenditure on fundamental homeopathic research. The only reason it is given any credibility is because so many people have staked their livelihoods in believing it. If Hahnemann had not been born two hundred years ago, but turned up at an NHS hospital today asking them to buy his pills, he would be unceremoniously thrown out for being an utter crank. And that is how we ought to treat homeopaths today.

The news this week has been filled with reports of the relative ineffectiveness of many antidepressant medications. The real shocker is how important data has not been made available to properly establish their effectiveness. Taking this science based medicine approach allows us to clearly differentiate between the different demands of whether more research is warranted into various sorts of antidepressants. Homeopaths may try to seek some equivalence between their failed and partially successful trials and the disappointing evidence for the effectiveness of some antidepressants. Both may look like placebos. But with the conventional pharmaceuticals, plausibility may still be much higher. We may not understand detailed mechanisms for how these drugs affect mood, but at least chemical intervention has some plausibility. My current glass of wine proves that. And, these drugs do show some effect for more depressed people. Understanding why this is and how these effects might be improved would look to be imperative. Homeopathy can make no such claim on limited research money.

And so to summarise, the Cochrane Review should limit its calls for further research to situations where plausible hypotheses exist, as without this, clinical data can never be persuasive. And for sceptics, attacking homeopathy cannot be done by solely by attacking the clinical evidence base. That evidence may well be poor and fragmented but there will always be a constant trickle of positive results such as the Oscillococcinum review, no matter how minor, that allow homeopaths to claim they are part of the evidence based medicine movement and that sceptics are being hypocrites. Homeopathy is wrong because the evidence that does exist is far too limited for us to accept its efficacy given the extreme implausibility of its action.

****************************************************************************

If you want to explore more of the ideas raised here, a new blog has recently started. ScienceBasedMedicine.org is being written by prominent sceptic bloggers such as Steven Novella, Wallace Sampson, Harriet Hall and David H. Gorski.

very elegant and well-argued piece. Just one minor detail …

‘The top right quadrant is indeed the quadrant of miracles in that we are being asked to accept something that appears to be against natural laws.’

This should be the top left quadrant, surely.

Thanks Paul. Corrected.

The phrase “more research is needed” seems to be being taken by homoeopaths as meaning “we think it works but more research is needed to prove this”, whereas in fact it means “it might work, but more research is needed if we wish to know if this is actually the case.” I think it was just carelessly worded. A better form of words might have been something along the lines of “but the evidence available is not sufficient to draw a definitive conclusion.”

Certainly, as regards “more research is needed”, given the standard of much homoeopathic research there is a very real risk that more research will just produce more false positives from poorly designed trials.

“More research is needed” probably means “I can’t prove it works yet, give me more money.”

Homeopathic duck’s liver – truly a quack remedy.

The link to the epetition is missing a ‘t’ on the end of it. Despite this I have managed to sign the petition and must thank you Canard Noir for bringing it to my attention.

Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary, but if homeopathy could show this extraordinary evidence (which it has not done), we would have to accept it, no matter what the plausibility is, in my opinion. But this is not the case: the evidence for homeopathy is far from abundant, and can be explained in other ways, such as cognitive biases and fraud.

Perhaps the graph needs another axis representing the ratio of the claimed magnitude of the therapeutic effect to the effect shown by even a very generous reading of the evidence.

Homeopathy is supposed to be able to cure every damn disease. The fact that even by cherry-picking the evidence the largest effects they can show are trivial is itself pretty damning.

Who said that Homeopathy cured “every damned disease”?

There are some narrow-minded comments on this website that have an overall damning effect on the article presented in terms of credibility.

The SoH and Registered Homeopaths see positive results in patients on an ongoing basis. Nobody is claiming miracle cures out there, as some patients have a long road to walk.

George Vithoulkas was awarded the Alternative Nobel Prize for Health in 1996 – have any of you achieved this on the quackometer?

I know who I would trust.

Ha Ha Ha – the alternative nobel prize?

The prize that has nothing to do with alfred nobel? The prize that rents the swedish parliament building in an attemt to give itself some qudos? Ha Ha Ha.

Have I won such a prize? No, I do not look for validation of my arguments from half-baked fake organisations.

Agree 100% with Elannaro – plausibility is not the overriding issue if the treatment can be shown to work. How it works doesn't really matter and can be worked out later.

Plenty of drugs have unknown modes of action but their efficacy is clear.

The problem with homeopathy and with most CAM therapies, however, is that when they are rigorously tested, they are found either not to work at all or to have extremely weak, trivial effects that are all but worthless.

You are forgetting that homeopathy works extremely well on both babies and animals. NEITHER can be coerced into faking their improvement. The improvements are realised without unpleasant, harmful side-effects, like a very high percentage of drugs regularly and generously prescribed.

Maybe Andy isn’t mentioning it in this very article, but the matter has been discussed at length on this website and elsewhere.

Let me give you a quick rundown:

1) You are underestimating the capacity of both animals and children to acknowledge that certain actions of the parent / keeper / doctor etc. are meant to make their pain go away. For an astonishing example of “animal reacting to expectations” searcg the web for the “Clever Hans effect”.

2) You are forgetting that the success of the ritual applied to the child or animal is usually reported by the person administering (or at least having ordered) the treatment.

2.a) Your baby stopped crying after you applied homeopathic teething relief? But maybe it would have stopped crying after a little while anyway? Maybe a little pure water would have done the trick, or the fact that you are giving the baby more attention now? Don’t fall for the “post hoc ergo propter hoc” fallacy and simple “regression to the mean”.

2.b) Same “attention” and “get better anyway” thing goes for animals. On top of that, in many cases the animals are treated with both conventional medicine and homeopathic solutions/pills – yet any success is attributed to homeopathy.

3) I’ve seen a lot of such studies, and they are usually using homeopathy alongside conventional treatment, or lack control groups, or don’t have statistical strength (or statistical analysis at all)… or all of that. In essence, the studies are poor and can (by their design!) not find effects of homeopathy.

4.a) Yes, you are right that many drugs that actually work also have side-effects. Sometimes annoying, sometimes harmful, and very rarely even fatal. On the other hand they have proven benefits and can improve quality of life, can actually heal diseases and may even save lives.

4.b) Homeopathy does none of that; it entertains the customer (be it adult, child or animal) until he heals himself (or until conventional medicine does the trick). And since there’s nothing in it, it also has no direct side-effect. However, your (or your practitioner’s) belief in the sugar pills may prevent you from seeking proper treatment, which may negatively impact your health. Homeopathy will not keep your diabetes in check (hell, it’s sugar, it may even do harm here), it will not protect you against malaria or Aids and it will not heal your cancer.*

Greetings,

Daniel

*) I have just recently read a systematic review of Chinese herbal medicine (which from the start has more plausibility than homeopathy) as a complementary treatment (i.e. as pain relief or to support the healing process) for breast cancer patients. The effects found were so small that they were hardly clinically significant. And mind you, the studies in the review were all carried out without placebo control, so a huge danger for bias exists. One must assume that there is no acutal, reproducible effect at all.