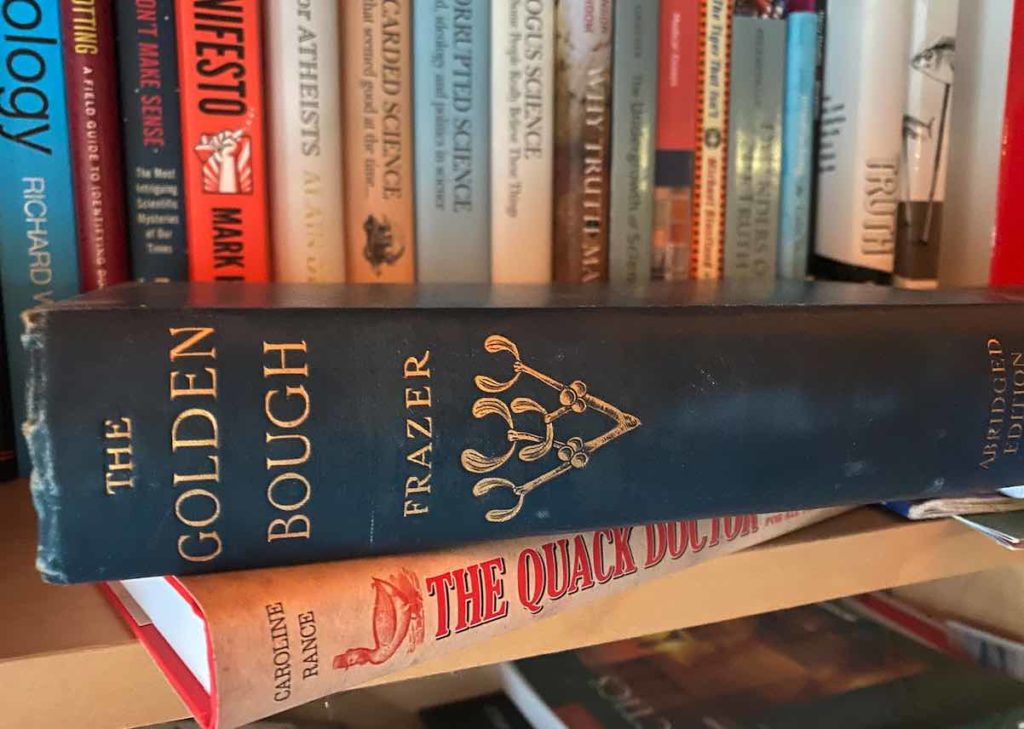

An essential read for any sceptic is the early 19th Century classic, The Golden Bough by Cambridge Scholar Sir James Fraser. Fraser set out to catalogue, describe and categorise the various forms of magic and religion around the world. It is a dense and rich book full of all sorts of traditions, beliefs, rituals and rites.

The book sets out the principles of Sympathetic Magic early on.

Sympathetic Magic is at the core of superstitious thinking. It arises from the belief that there are ‘actions at a distance’ and ‘invisible connections’ between things in this world. One thing can act on, or change another thing through some invisible “sympathy”.

Sympathetic Magic can be broken down into two divisions: firstly, homeopathic magic, and secondly contagious magic. Homeopathic magic is the idea that if one thing resembles another thing, then it becomes that thing or can influence that thing. It is Imitative Magic.

Contagious Magic is the idea that if one thing has been in contact with another thing then some essence of that contact will remain and influence that thing. We might all be happy to wear second hand clothes – but not if they had belonged to a serial killer.

Homeopathy, confusingly, relies on both types of magical thinking. Firstly, the mantra of “like cures like” is clearly the archetype that Fraser relied on. Homeopaths believe that if a substance can cause certain symptoms in people (like make you vomit), then that substance can cure you of diseases that make have those symptoms.

Homeopathy also relies on the second principle of contagious magic. The ‘medicine’ is diluted to such incredible degree that the solution can no longer contain a single molecule of that substance. But the ‘remedy’ will contain a memory of that substance – an “essence”.

Which is a good thing, as much of what homeopaths use is really poisonous, noxious or infectious. But an intangible and powerful force will remain and exist in the remedy as a result of the ritualistic preparation. Nothing more than the ‘word’ remains.

But homeopathic thinking exists in many cultures, superstitions and rituals. Fraser notes how Scottish fishermen would throw one of their members overboard if they were catching no fish. Their unfortunate crew member would become the first fish they would catch that day.

Fraser describes how the “Warramunga” in Australia would perform a pantomime of the witchetty grub emerging from its chrysalis to encourage a bountiful supply in their foraging. They may wear head-dresses to resemble the emu to bring success to their hunting. A common theme in these magic rituals is that if the shaman and participants dress in a manner to resemble the object of their ritual, they will become that thing for the ritual and be able to influence their own destiny. The ritual hunt will become a successful real hunt.

Contagious or contact magic is where transformations can take place when there is a physical connection between two things that may persist after separation. Religious relics are an obvious example, but today we might see someone owning a professional footballer’s shirt in the belief that it may make them better at the game. Fraser notes many traditions of how walking in someone’s footprints may be used to influence them for better or worse.

Pythagoras warned us to smooth out our bed to remove our imprint. Someone being in our space may do us harm.

These simple principles of magical belief explained so many customs and rituals across many societies and time for Fraser. Of course, now, we live in more enlightened times where such superstition plays no role in our lives.

Or do we?

A very useful summary but I think that you mean early 20th Century. I’ve had a cheap hardback copy for over two decades and keep going back to it regularly for education and entertainment.

the Golden Bough is a wonderful book(s). originally 13 volumes :

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Golden-Bough-Set-Palgrave-Archive/dp/0333977084

one of my dad’s favourites and forever fascinatinG