Continued from Breaking Down Cass Review Myths and Misconceptions: What You Need to Know: Part 1

The Myths (Part 1) …

Myth 1: 98% of all studies in this area were ignored

Myth 2: Cass recommended no Trans Healthcare for Under 25s.

Myth 3: Cass is demanding only Double Blind Randomised Controlled Trials be used as evidence in “Trans Healthcare”

Myth 4: There were less than 10 detransitioners out of 3499 patients in the Cass study.

The Myths (Part 2)…

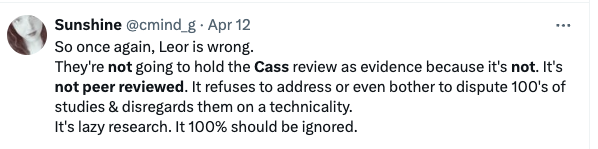

Myth 5: The Cass Review is worthless because it is not Peer Reviewed

Myth 6: The proposed service is based on the idea that brains don’t reach maturity until 25.

Myth 7: Most other systematic reviews and clinical guidelines disagree with Cass.

Myth 5: The Cass Review is worthless because it is not Peer Reviewed

Fact

It is true that the Cass Review is not a peer-reviewed research paper, but that does not mean it is worthless or lacks meaningful status. The Cass Report was commissioned by NHS England as an independent review of the services available in the NHS for children with gender identity issues. Consequently, it was designed to inform future public service provision. As part of the review, Cass itself commissioned other teams to conduct research programs and publish their results in peer-reviewed journals so that its recommendations could be based on the latest peer-reviewed studies.

Explanation

Peer-reviewed research papers are primary sources of information in academic literature. They undergo an evaluation process by experts in the field before publication to ensure the reliability and credibility of any findings. These papers can then be used to shaping future research directions or inform evidence-based practices in various fields, such as medical practice and social policy.

The Cass Review does not constitute a primary research study. Instead, it serves as a secondary study aimed at drawing conclusions regarding a specific policy area – in this case, NHS Service Provision. It achieves this by conducting an analysis based on mostly primary peer-reviewed literature. The review synthesises existing research findings from peer-reviewed studies to inform its conclusions and recommendations within the targeted policy domain.

The Cass Review stands as the most extensive independent examination of issues surrounding topics such as puberty blockers in children, and took four years to completion. During this time, it commissioned other researchers to conduct new primary research, thus expanding the breadth of peer-reviewed literature on the subject matter. This was done to ensure the currency of the primary literature, and ensuring it addressed the specific questions needed by the Review.

The University of York, on the request of Cass, undertook a series of related studies to look at “epidemiology, clinical management, models of care and outcomes”. Also, studies looking at the range of clinical practices and standards being used around the world to see if common best practices were followed and how they were arrived at. These studies were peer reviewed and published in the Archives of Disease in Childhood, an international paediatric journal from the BMJ and RCPCH.

Details of all peer reviewed studies commissioned by the Cass Review and used to inform policy recommendations

Systematic Reviews

Characteristics of children and adolescents referred to specialist gender services: a systematic review Jo Taylor, Ruth Hall, Trilby Langton, Lorna Fraser, Catherine Elizabeth Hewitt

Impact of social transition in relation to gender for children and adolescents: a systematic review Ruth Hall, Jo Taylor, Catherine Elizabeth Hewitt, Claire Heathcote, Stuart William Jarvis, Trilby Langton, Lorna Fraser

Psychosocial support interventions for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review Claire Heathcote, Jo Taylor, Ruth Hall, Stuart William Jarvis, Trilby Langton, Catherine Elizabeth Hewitt, Lorna Fraser

Interventions to suppress puberty in adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review Jo Taylor, Alex Mitchell, Ruth Hall, Claire Heathcote, Trilby Langton, Lorna Fraser, Catherine Elizabeth Hewitt

Masculinising and feminising hormone interventions for adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review Jo Taylor, Alex Mitchell, Ruth Hall, Trilby Langton, Lorna Fraser, Catherine Elizabeth Hewitt

Care pathways of children and adolescents referred to specialist gender services: a systematic review Jo Taylor, Ruth Hall, Trilby Langton, Lorna Fraser, Catherine Elizabeth HewittInternational Guidelines

Clinical guidelines for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review of guideline quality (part 1) Catherine Elizabeth Hewitt, Jo Taylor, Ruth Hall, Claire Heathcote, Trilby Langton, Lorna Fraser

Clinical guidelines for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review of recommendations (part 2) Jo Taylor, Ruth Hall, Claire Heathcote, Catherine Elizabeth Hewitt, Trilby Langton, Lorna Fraser

International Survey

Gender services for children and adolescents across the EU-15+ countries: an online survey Ruth Hall, Jo Taylor, Claire Heathcote, Trilby Langton, Catherine Elizabeth Hewitt, Lorna Fraser

The Cass Review is similar to other documents in gender care that seek to set out policies and best practices and these are also not peer reviewed. The World Professional Association of Transgender Healthcare (WPATH) has influenced many countries and gender clinics around the world with its policy recommendations. It is not peer reviewed. Furthermore, it is not independent, unlike Cass, as it is governed by members who are professionals in the field and could potentially gain from recommendations that promoted their type of work.

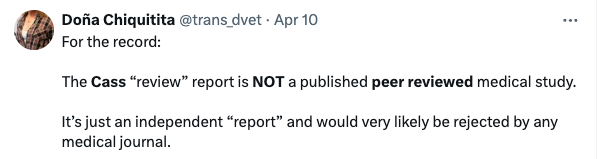

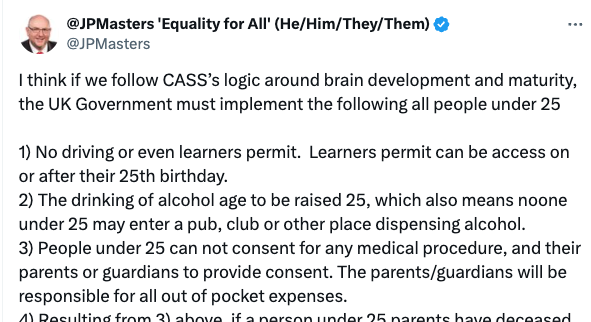

Myth 6: The proposed service is based on the idea that brains don’t reach maturity until 25.

Fact

The Cass report does not assert that brains do not reach maturity until a person is 25, nor does it suggest that individuals under 25 cannot make informed decisions about their healthcare. The significance of the age of 25 stems from a recommendation advocating for continuous provision of services from early years up to this age. This approach aims to prevent patients from experiencing a discontinuity of service during critical periods of sexual, physical, and brain maturation.

Explanation

The Reviews goes into great detail in several sections about the significance of the maturing brain in gender medicine. Cass states that an “understanding of brain development and the usual tasks of adolescence is essential in understanding how development of gender identity relates to the other aspects of adolescent development.”

Perhaps a source of the myth comes when Cass says,

It used to be thought that brain maturation finished in adolescence, but it is now understood that this remodelling continues into the mid-20s as different parts become more interconnected and specialised (Giedd, 2016)

Cass Review, p102

The approach is cautious in these statements and setting a picture of how adolescents may not alays make great decisions about themselves,

By the age of 15 an adolescent will make similar decisions in relation to hypothetical situations as an adult. However, although adolescents can balance the possible harm or benefit of different courses of action in theory, in the real world they may still engage in dangerous behaviours, despite understanding the risks involved.

Cass review, p103

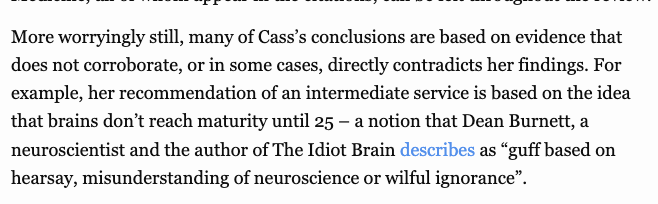

Dean Burnett, the academic and author known for his popular neuroscience and psychology books like “The Idiot Brain,” highlighted in some tweets that the notion of the brain not fully developing until the age of 25 is ‘utter guff, rooted in hearsay, misunderstandings of neuroscience, or wilful ignorance’. He raises valid points about the ongoing development of the brain.

However, it’s essential to clarify that Cass does not assert that patients must reach the age of 25 before their brain development renders them competent to make decisions about healthcare. Instead, the context emphasises an evolving maturation process, wherein perspectives may shift during adolescence and beyond.

The implication is evident: decisions made at a young age regarding irreversible medical procedures may not necessarily stem from a stable and consistent worldview.

In Myth 2, I outlined the reasons behind extending service provision from childhood to the age of 25, and I won’t reiterate them here. It’s worth noting that this extension has no connection to brain maturation.

Myth 7: Most other systematic reviews and clinical guidelines disagree with Cass.

Fact

A small number of applicable systematic reviews on paediatric gender medicine exist, and none of them conclude that care standards can be based on high-quality evidence. This aligns with the findings of the Cass Review. Additionally, the Review commissioned new research to compare various international approaches to best clinical practice and service provision. The quality of clinical guidelines was assessed using best practice scoring methods such as AGREE II, revealing poor standards. Critically, Cass uncovered evidence of circularity, with organisations referencing each other to justify their approaches. Consequently, the consensus is likely to be illusory

Explanation

The Cass Review sought to see if other national guidelines could be adopted or adapted as the basis for English guidelines. This obviously might save a significant amount of work and allow shared experience and re-use of research.

In order to do that, Cass had to evaluate if existing standards around the world were based on sound evidence and rational and ethical responses to that evidence. There are existing methods for researchers to evaluate the quality of clinical guidelines and service provisions.

Guidelines were scored by an established standard to assess their quality. They were rated on areas such as stakeholder involvement, rigour, clarity, applicability and editorial independence. 23 guidelines were appraised.

Details on the AGREE II tool to assess quality of standards of care.

The AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) is a tool designed to assess the quality and reporting transparency of clinical practice guidelines. It provides a standardized framework for evaluating guidelines across various healthcare domains.

The AGREE II tool consists of 23 items organized into six domains:

Scope and Purpose: This domain assesses the overall aim, specific objectives, and target population of the guideline.

Stakeholder Involvement: It evaluates the extent to which the guideline development process involved relevant stakeholders and incorporated their perspectives.

Rigor of Development: This domain focuses on the methodology used to develop the guideline, including systematic methods for searching and selecting evidence, and methods for formulating recommendations.

Clarity of Presentation: It assesses the clarity, accessibility, and comprehensibility of the guideline, including its structure, language, and format.

Applicability: This domain evaluates the potential barriers and facilitators to guideline implementation, as well as strategies to improve uptake and dissemination.

Editorial Independence: It assesses the extent to which the guideline was developed free from bias or undue influence from funding sources or other conflicts of interest.

Each item within these domains is rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating better quality. Reviewers use the AGREE II tool to systematically evaluate guidelines, providing scores and comments for each domain.

The AGREE II scoring method helps healthcare professionals, policymakers, and guideline developers assess the quality of clinical practice guidelines, facilitating informed decision-making and promoting the use of high-quality evidence-based practices in healthcare.

Key findings were that (quoting from the report),

- Only the Finnish guideline (Council for Choices in Healthcare in Finland, 2020) and Swedish guideline (Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, 2022) scored above 50% for rigour of development

- Only five guidelines described using a systematic approach to searching for and/or selecting evidence (AACAP 2012, Endocrine Society 2017, Finland 2020, Sweden 2022 and WPATH 2022).

- Most of the guidelines described insufficient evidence about the risks and benefits of medical treatment in adolescents, particularly in relation to long-term outcomes. Despite this, many then went on to cite this same evidence to recommend medical treatments.

- Two international guidelines, the Endocrine Society 2009 and World Professional Association for Transgender Healthcare (WPATH) 7 guidelines influenced nearly all the other guidelines.

Crucially, the Endocrine Society and WPATH guidelines cited each other as their sources of evidence. This created a circularity of references with most other guidelines based on this ungrounded approach. This could give the illusion of consensus when in fact the evidence base was very poor and disregarded in guidelines.

And importantly,

Only the Swedish and Finnish guidelines differed by linking the lack of robust evidence about medical treatments to a recommendation that treatments should be provided under a research framework or within a research clinic. They are also the only guidelines that have been informed by an ethical review

Cass review, p130

conducted as part of the guideline development.

Cass looked in detail at the WPATH guidelines since they appear to be so influential and touted as the “gold standard’. She found the evidence review WPATH commissioned to inform its version 8 guidelines also came to the conclusion the evidence base had a “high risk of bias in study designs, small sample sizes, and confounding with other interventions.” This is not dissimilar to the findings of Cass.

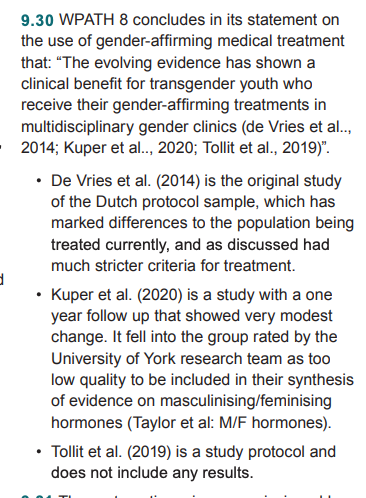

In its recommendation, WPATH failed to reference its own systematic review that concluded the evidence was and instead claimed “The evolving evidence has shown a clinical benefit for transgender youth who receive their gender-affirming treatments in multidisciplinary gender clinics.”

It is worth quoting Cass in fill about how WPATH used selective evidnece to justify its guidelines,

On a personal note, I have to say the WPATH guidelines can only be read as deeply dishonest or utterly incompetent.

What we can see positively is that other countries that have conducted quality systematic reviews come to similar conclusions about clincial guidelines and that “that treatments should be provided under a research framework or within a research clinic.”

We can see that when other bodies appraise the evidence base fairly, create guidelines under independent ethical review, and are themselves independent of financial and professional outcomes, they agree with Cass.

I hope you will never delete or edit these articles so that future generations can laugh directly at d1psh1ts like you.

How ironic.

Your cogently argued evidence filled reply is awaiting peer review.

ERROR! no argument found.

RESULT laugh at Eastern Wanderer